The following blog post is based on a conversation between Stuart ‘The Wildman’ Mabbutt and William Mankelow. This conversation featured on an episode of their podcast: The People’s Countryside Environmental Debate Podcast. The episode, titled ‘Timing, Speech, Protest, Freedom’, was released on the 4th of July, 2023, and you can listen to it here on Podfollow, Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, or Spotify.

This blog post was transcribed from audio form and edited by Suzi Darrington, a Crankstart Scholar and intern from Oxford University’s Careers Service, who worked with Stuart between the 3rd of July and the 11th of August in the Summer of 2023. The Crankstart Scholarship provides financial support to students from low-income households, alongside unique internships, volunteering opportunities, and events throughout the year. Scattered throughout the blog post will be her Intern’s Insights. These comments are added post-recording after creating the transcript, and do not represent thoughts vocalised by Stuart, William, or Suzi on the podcast.

| Intern Suzi’s Insights (during the transcription process) will be displayed like this. Suzi wasn’t present during this charade. |

Is there a time and a place for protest?

© PA Wire

Stuart: “We’re back! It’s a hell of a long question today, but we’ll move on to that in a little bit. This is The People’s Countryside Environmental Debate Podcast. I’m Stuart the Wildman Mabbutt, and hopefully you’ll learn something new today, or think about something in a new way. Today’s question is about the death of Queen Elizabeth II and the right to protest. Who’s the co-host?”

William: “I’m William Mankelow! Thanks very much for being with us. I’m a photographer, so I’m often behind a camera or a microphone, flying a drone, or in front of a live audience. That’s where you’ll find me: the four habitats of the Mankelow.”

Stuart: “June and July are a little bit quieter for us, having had a hectic May down in Wiltshire, as well as doing the live incarnation of this podcast in Oxfordshire. It’s just nice to have a bit of quiet time.”

William:“ Does it feel good to have those two big bits of work in our back pocket now?”

Stuart: “In a way, but I move on very quickly, so it doesn’t necessarily feel good or bad. It’s just done. It feels good to actually have a bit of a rest, though. Anyway, in this podcast we engage in the conversations that need having. We try to keep the big issues in your and our consciousness’, and we try to come up with some actions for you to take.”

William: “We do!”

Stuart: “We tend to have meandering conversations, a little bit like what you’d expect of two men sitting in a pub. I’d be on a pint of Guinness with a whiskey chaser. What would you be on?”

William:“Probably a pint of coke. Depending on what time of the day it is, I might be on an IPA.”

| Suzi: I think I’d have a lemonade, or a glass of white wine. |

Stuart: “I can’t think of anything worse. Anyway, take a deep breath, William, because Molly in Oxford, England has sent us a mega question. Now, it’s so long that we can’t fit the whole thing in the description of this episode, because it breaks the word count, so we’ll only have part of it down there. The rest will be on a Google Document, linked down below.”

William: “Thank you, Molly, for your question, and thanks for reducing it slightly as well.”

Stuart: “Yes, I was going to say that. I was talking to Molly via my Wildman Productions Facebook page over the weekend, and she reduced her question right down, but the problem is that if we cut anything else out we lose some key points. Thankfully, Molly answers a lot of her own points. So, William, have a go at starting.”

William: “I would suggest that you pause the podcast now, go and make yourself your favourite hot drink, come back, un-pause the podcast, and then start listening to the question. I’ll let you go away… Right? You’re back? Okay, here is Molly’s question.

Please explore the right to protest and the right to grieve. I ask this after seeing BBC footage of Queen Elizabeth II’s funeral in Scotland. Her coffin was transported by road, and there were a few anti-monarchy protests. There were, as I recall, four arrests in Aberdeen and Edinburgh. One individual heckled Prince Andrew and was bundled away, but the media didn’t give too much coverage to it, or the other protests. There were protesters in Edinburgh saying that they’d been arrested, then de-arrested away from the site, claiming that they were told it wasn’t the time or place; another example of the state dictating where, when, and what people can and can’t say – an attack on the right to protest.

| Suzi: The fact that there was little coverage of the protest was, in my view, a decision made not to protect people’s feelings, but to cover up the anti-monarchy sentiment in the UK. This is why they didn’t broadcast much of the protesting at the coronation too, though the shouting was quite difficult to cover up in some places. |

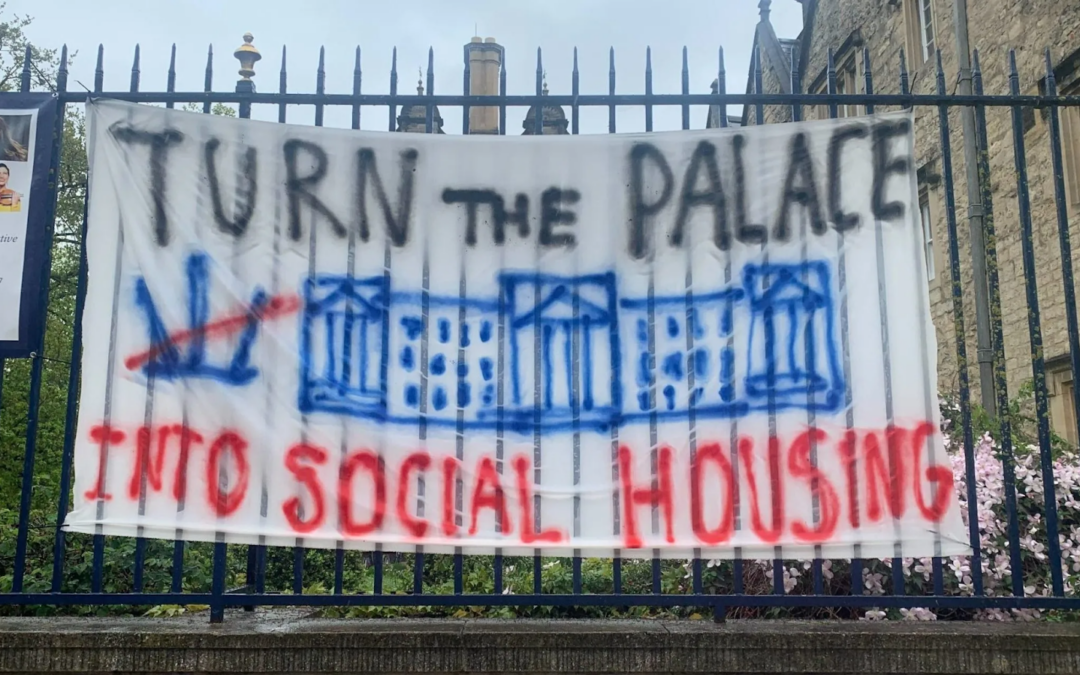

William: One protester claimed that the protests were largely peaceful, with people holding up signs saying ‘Not My King’. They also claimed that people were being arrested for simply holding blank paper that could be written on and used as part of a protest. Some protesters that were interviewed said this was an attack on freedom of speech, and that they just want to have a conversation about whether or not an unelected monarch still has a place in the UK.

Some BBC footage appeared to show a grieving member of the public trying to engage with protesters, but it appeared one protester refused to look at them, instead turning sideways and reiterating their right to protest. This felt passive aggressive, and not conducive to dialogue. I didn’t really hear what was being said, but wasn’t this an opportunity for the conversation that they wanted?

© The Oxford Blue

William: At the proclamation of the new king in Oxford, one protester kept shouting ‘down with the king!’. They were told by a pro-monarchist to ‘shut up’, and when they were interviewed on TV, they claimed that being told to ‘shut up’ was an attack on their freedom of speech and their right to protest. It did make me smile that one could argue that for people not to be able to tell them to ‘shut up’ could be an attack on their freedom of speech as well.

I think that we need to be careful to not interpret freedom of speech as the ability to say what you want, whenever you want, wherever you want, to whoever you want. It’s not just about can we speak, it’s also about should we speak. As you often say on the podcast, it’s not what you do, it’s how you do it. We need to retain self-censorship alongside freedom of speech and pick our battles wisely. If we just speak up whenever we like, it becomes ineffective, inconsiderate, offensive anarchy.

Timing protests for when one’s audience is more receptive makes more sense. The art of good marketing, getting their message out, received, discussed, considered and acted upon, is surely what protesters are aiming at. I’m not sure that raising the anti-monarchist debate during a time of mourning is great timing, because the public are emotionally whipped up by the media, telling us it’s a sad and somber time, when everyone feels a sense of loss. I say this without being a royalist, however I don’t want to be aligned with these particular ill timed protests.

| Suzi: Maybe it was bad timing, or maybe it was good timing. The monarchy was getting heavy coverage at the Queen’s funeral, and letting it go without protest might signify an acceptance of, or respect for the monarchy, which republicans might not want to put across. When the cause is ‘unpopular’ (which republicanism isn’t, really), it might feel as though there is no ‘right time’ or ‘right way’ to protest the cause. |

William: Moreover, I do think that the late Queen did a great job of finding the middle ground. I respect her commitment and work ethic, and her ability to connect with people in an apolitical way.

| Suzi: The image of the leading monarch as someone ‘hard-working’ is one that is readily accepted, but that I think should be challenged. Their work is largely ceremonial, and a far cry from the labour that people from working backgrounds perform every single day in this country, receiving only a fraction of the wealth they generate. Attitudes towards the monarchy vary with political affiliation, with Conservatives having a much more positive outlook on the institution than Labour voters, suggesting that the Queen might not have been as apolitical a figure as some assume. Additionally, the monarchy itself is not an apolitical institution. Whilst the leading monarch might avoid abusing their legal right to prevent bills passing through the requirement of ‘Royal Assent’ out of respect for an unspoken rule, the monarchy is a powerful lobbying institution with the soft power to influence bills and legislation well before they appear in parliament. One look at the list of donors on the Royal Family’s website reveals that they are absolutely not ‘politically neutral’ – their interests are very tied up. |

William: In the UK, we live in a republic under a veil of monarchy. Maybe we can’t face having another go at removing the monarchy when the first attempt went so wrong. I refer to Oliver Cromwell acting as Lord Protector, who then progressed to acting and dressing like a monarch. After he died and the monarchy was reinstated, his body was exhumed and his head was placed on a spike outside of Parliament for four years. It would be great to have a role for someone like the Queen, but not in the form of an unelected monarch that is eating huge amounts of public funds.

As an aside, was there something more sinister going on with the policing of these anti-monarchist protests? The quick removal of protesters has been interpreted by some as the state dictating what we can or can’t say, do, and think. Is that what was going on? Or were they instead trying to mitigate the security risk of having two polarised groups, and the need of a party potentially willing to explore the middle ground? I didn’t see the police cracking down on all the protests, but I did see them using their judgement on a case by case basis as to what was appropriate and what wasn’t.

| Suzi: We should be suspicious of policing, following the passing of the Public Order Bill. |

William: I’d like to end by saying that it’s interesting that Queen Elizabeth II will go down in history all over the world as The Queen. Although I don’t agree with her title, I admire her as a person and she achieved so much. Let’s hope her example isn’t lost in history.”

Stuart: “Well done William for getting through that.”

William: “I think you must have done a couple of edits through there, because there were a couple of words that I did stumble upon.”

Stuart: “I think Molly answers a lot of her own points, but let’s discuss protest and the right to grieve. I do think that, regardless of whether the media whipped us up into sadness by all the coverage of the funeral, I would want to question the timing of this. If you protest at this point, you’re going to get a higher percentage of negative feedback, with less time for dialogue. I think the conversation needs to happen away from this.”

William: “Particularly from somebody who is really mourning the passing of someone that they admired, who was a special person in their life… I mean, if this was more of a personal thing, as in, if it was somebody very close to you who had died, and there was somebody else in your family who wanted to raise a grievance about them, the period of mourning the funeral is not the time and place to do it, is it? I think the anti-monarchists’ aim was to cause as much difficulty and potentially even pain as possible. They must have known that people were going to be upset by it.”

| Suzi: Potentially, the fact that people were so upset by the Queen’s passing, as though she were a relative rather than a public figure, was something that the protestors wanted to draw people’s attention to. The parasocial relationship which many people, especially those from older generations, had with the Queen was understandable but bizarre. |

Stuart: “I’m an anti-monarchist, but I’m like you Molly, I think the timing is ill-advised. You do point out that some protesters were saying that they were arrested and then de-arrested away from the site, with police claiming that it ‘wasn’t the time and place to protest’, but that’s a tactic the police do. They remove you from the situation and then arrest you. That’s just a tactic they use, you know? It’s just a fact.”

William: “They use that in every protest. They used that in the HS2 protest scene around Euston Station, didn’t they?”

Stuart: “Yeah. What else jumped out at me… Freedom of speech! Yes, I agree with what you’re saying: freedom of speech isn’t about saying what you want, when you want – you need to time it.”

| Suzi: Free speech is not about whether we should or shouldn’t speak as Molly suggests; it’s about whether we have a right to speak. She is right that it’s not as simple as saying whatever you want, whenever you want, but speech causing offence is legally still considered free speech, as long as it’s not classed as hateful. It is right that ‘offensive’ protest at a public event should be classified as free speech. |

William: “At the protest in Oxford, there was a guy who, in a way, was being removed by the police for his own protection, because there were probably more people there that were pro-monarchists than not. There may have been a few people who were just bystanders, but there also would’ve been people that turned up specifically for the proclamation.”

© Shutterstock

Stuart: “That’s a good point… And the people that he was told to shut up by, although he’s saying they shouldn’t be telling him to do that, were exercising their right to freedom of speech, if you have it both ways.”

William: “It’s freedom of speech, yeah. So in a way you could actually argue that somebody saying, not my king, is actually a way of standing there and saying, shut up! Not interested.”

Stuart: “It’s freedom of speech. You want to stand up and say ‘not my king’, but if that’s fine then what’s wrong with somebody else saying ‘shut up’? It’s just the timing. That was the biggest point, and you covered it quite concisely. What else was there…”

William: “There is a line here that says: ‘We need to retain self-censorship alongside freedom of speech and pick our battles wisely. If we just speak up whenever we like, it becomes ineffective, inconsiderate, offensive anarchy.’ I agree – sometimes you do need a bit of self-censorship, because there are times and places to say things.”

Stuart: “She raises the point that marketing correctly brings you more business, that’s what the protesters are doing. They are trying to get their message across, received, and discussed. If you don’t self-censor and pick your time properly, it’s going to impact you on that end. So they should market their message.”

| Suzi: Protestors are trying to make change, regardless of whether people agree with them. I doubt the suffragettes were aiming to bring men (or other women) on side through their protest methods. Many of their protest methods were a way of trying to force change through fear. Similarly, Just Stop Oil are bringing attention (much of it negative) to their cause by constantly getting in the news. They are also making people frustrated. One way to stop their protests is to ‘give in’ to their demands of no new oil and gas. |

William: “To be clear about it, market at the right time. I say that because there were protests at the coronation, and I think that’s a more appropriate time and place to protest, because no matter what your feelings are about the royal family, that’s a mother who has just died. That’s a grandmother who has just died. So that’s that. It is a little bit insensitive, and I think the timing was done on purpose to cause people pain. They must have known the reaction they’d get.

I think, in that instance, we become more polarised on this issue. The polarisation caused shows the protestor’s feelings – ‘Oh, they’re monarchists, they deserve it.’ If you’re anti-monarchist, you could be really extreme, and you might think that monarchists are stupid for believing in the monarchy.”

Stuart: “There was something that popped into my head about three days later, when the coronation had finished. There was an item on television about the cost of living, about people struggling. You can’t help but think that, three days ago, there was a bloke and a woman sitting in a golden carriage, going through London, and now we’re talking about the cost of living crisis. That grates me about the monarchy. It’s the haves and have-nots.”

| Suzi: This is the big problem with the monarchy. Fundamentally, they are a group of people divinely entitled through their blood (and nothing more) to immense privilege and riches. |

William: “Yeah. I wouldn’t class myself as anti-monarchist. I’d say I’m quite apathetic about it.

There’s a bit here saying that ‘the late queen did a great job finding the middle-ground’, and that she had ‘commitment, a good work ethic, and an ability to connect with people in an apolitical way’.”

Stuart: “I think what Molly is talking about there is that, during COVID, the Queen did a speech to the nation. I think that was quite useful, because a politician sat there saying the same words wouldn’t have resonated in the same way.”

William: “Because he was detached from it… You didn’t really know her as a person.”

Stuart: “I appreciated that, having been in complete isolation. I don’t think I’ve ever actually processed those lockdowns fully, but I think that’s what Molly’s referring to there, the Queen’s ability to connect with people in an apolitical way that few others could, is bang on.”

© Beyond Belief Archive

William: “Yes. And, of course, going on to talk about Oliver Cromwell…”

Stuart: “‘We’re a republic under the veil of a monarchy’, she said. But there’s humour in this, isn’t there?”

William: “There is a bit of humour. The whole thing with Oliver Cromwell is that he actually ended up being a monarch himself, as you were saying here, Molly. I have heard pro-monarchists say that, if we became a republic with an elected president, we could end up with our own Donald Trump, but it goes the other way as well. Who’s to say that we wouldn’t end up with a Donald Trump King or Queen?”

| Suzi: And a King or Queen Trump would be even worse, because you wouldn’t be able to remove them. They are not responsible to the legislature, and they have legal privileges that allow them to override democratic decisions made by an elected parliament. |

Stuart: “Yeah.”

William: “Right now, we have a relatively stable-minded King, I would say. He’s not going to rock the boat, is he? We don’t know who’s going to come through in later generations, though.”

Stuart: “I mean, the humour for me in this is that maybe we can’t face having another go at removing the monarchy when the first attempt went so wrong. These are some very good points. Molly also asks whether there was ‘something more sinister going on with the policing of these anti-monarchist protests’. Was the quick removal of protesters an example of the state dictating what we can and can’t say, or were the police simply trying to manage the risk? On some level, I think there could have been something sinister going on, but there was also a balance to be struck between freedom of speech and preventing anarchy on the streets. There was a bit of both going on, I think.”

© CNN

William: “Maybe, just thinking about how people see King Charles as opposed to his mum, Elizabeth was a very remote figure, wasn’t she? A lot of people, especially in the later years, saw her as an extended member of the family, like a grandmother. Whereas we’ve known Charles for many years. It’s almost like he’s… well, I wouldn’t use the word normal, but he’s just some guy, some dude, for me, if that makes sense.”

| Suzi: The fact that the Queen was a Queen rather than a King perhaps led us to see her as less of a ‘leader’, more of a family figure. We may have perceived her as being less powerful than she really was, and thus had more positive feelings about her. |

Stuart: “He’s the first monarch who we’ve been able to watch grow up through the media. In her final point, Molly says, ‘it’s interesting that Queen Elizabeth II will go down in history all over the world as the Queen. Not the second, not the first, just the Queen. Although I don’t agree with her title, I admire her as a person, and she achieved so much. Let’s hope her example isn’t lost in history.’ It’s interesting, she was the Queen. I think that’s something to do with the fact that she was there for so long, and that modern media just infiltrates our heads so readily.”

William: “It’ll be interesting to see what her period of time is going to be called, because you can’t call it the Elizabethan period, can you? The Elizabethan period was the first Elizabethan.”

Stuart: “People are saying Elizabethan right now, but I think the title of the period will be done in a few years time, looking back a bit more than it is now.”

William: “Yes, exactly.”

Stuart: “Do you still feel like we’re in it? Anyway, there are so many ways you can look at this, but Molly, I think you’ve answered a lot of your own points here, and I think it was worth reading through, because it made me think about things more thoroughly.

William: “Yeah, I agree.”

Stuart: “Anyway, thank heavens! The next question is from Peter in Sweden. I’ll let you pronounce Ostergudlund. It will be a much shorter question, so we’ll look forward to that. Hopefully our listeners will think about the issue discussed today slightly differently from now on. Is there an action you think we can raise from this, William?

William: “Look at how polarisation in your own life can affect your thinking. Don’t necessarily be ready to agree with everything everyone else says, but if you listen to people and take on board what they’re saying, you may find yourself agreeing with others a lot more than you disagree with them. “

Stuart: “Then, you can find some resolution from that conversation. My action would be to not readily have a cynical interpretation of what’s in front of you, or how it’s being policed. I do have this suspicion of an undercurrent of control going on, but I wouldn’t draw it like a gun too quickly, saying ‘the police are suppressing us’, and all the rest of it. View the world in a more balanced way, and if it comes out that we are being suppressed, fair enough, but let’s not start with that.

| Suzi: Be open to other ways of thinking! |

Stuart: Anyway, this has been The People’s Countryside Environmental Debate Podcast. We often don’t talk about the countryside, because we jump about all over the place, but that’s where you, the listeners, want us to go! I think the societal construct of monarchy is part of environmentalism, though.”

William: “It’s all part of the human condition as well.”

Stuart: “Exactly! So, in two days, we’re giving a talk over at Great Milton in the afternoon, in Oxfordshire . Come along to that, and tune into our next podcast episode. We’re on all the main platforms, Sundays and Tuesdays 10 a. m., with the occasional bonus episode. I’ve been Stuart ‘The Wildman’ Mabbutt. He’s been William Mankelow.”

William: “Thanks very much for being with us. In the next episode, we’ll be in Sweden, won’t we?”

Stuart: “Indeed! Get your ski jacket on, it might be a bit cold…”

If you’re interested in listening to The People’s Countryside Environmental Debate Podcast, you can tune in on Podfollow, Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, or Spotify.

This transcription was created with the help Crankstart intern Suzi Darrington from the University of Oxford.

Recent Comments